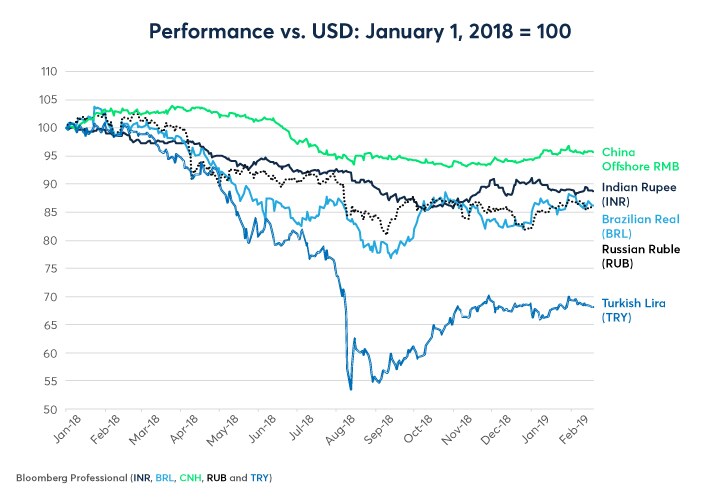

The Chinese renminbi and Indian rupee weathered last year’s emerging market turbulence with greater aplomb that currencies of the other BRIC members, the Brazilian real and Russian ruble (Figure 1). While India’s currency enjoyed a relatively calm 2018, the general elections coming up in April hold out the possibility of a much more challenging year for the rupee.

In the months prior to the India’s last election in April 2014, the rupee strengthened by 20% versus the U.S. dollar and by about 15% versus the euro in anticipation of the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) landslide victory. Indeed, the 2014 election produced a humdinger of a result. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s BJP party went from 116 seats to 282 seats in India’s lower house of Parliament – 10 more than needed for a majority. Combined with allies BJP’s majority totaled 64 seats. In fact, it was the first time that any party achieved an outright majority since 1984.

What drove the currency market’s pre-election optimism was hopes for radical reforms to land laws, taxes and labor markets that would allow India’s economic growth to rival that of China during the 1990s and 2000s. The currency market’s celebration, however, lasted about one month after the polls. Since then, the rupee has fallen by about 20% against the U.S. dollar. It also fell by about 12% versus the renminbi but has outperformed commodity currencies such as the real and the ruble by about 30% and 40%, respectively. Unlike Brazil and Russia, China and India are not reliant on commodity exports, so moves in raw material prices have less impact. In fact, lower oil prices were helpful to India, reducing the need for fuel subsidies as it freed up money for other budget priorities.

Modi’s economic reforms have produced mixed results so far. On the positive side, Modi opened numerous industries to foreign direct investment, including infrastructure. In 2017, he also managed to get the Goods and Services Tax enacted, which rolled a byzantine system of 17 separate taxes into one. He has also made progress towards simplifying India’s notoriously complicated administrative structure.

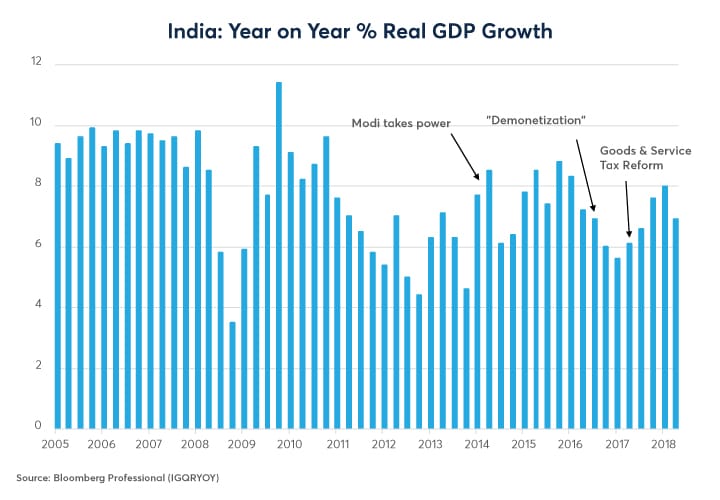

Other reforms didn’t turn out as hoped for. His administration backed off some labor market reforms following protests. Unable to gain passage of land reform, he attempted to impose it by executive fiat but later had to let his order lapse. The true disaster, however, was a reform that he never campaigned on and implemented seemingly on a whim: demonetization. Demonetization was an attempt to force the informal, cash-based economy into the banking system by getting rid of 500- and 1,000-rupee denominations essentially overnight. This reform wasn’t devastating for the economy, though it did slow growth temporarily (Figure 2). Demonetization’s main cost was political. It proved highly unpopular among the owners of small businesses who had formed part of the nucleus of his support and led to accusations that it increased inequality by favoring larger businesses and the wealthy.

The BJP has slid in the polls (Figure 3). So far, all but one survey shows the party still winning more seats in 2019 than any other individual party, but since demonetization few polls suggest that BJP will win an outright majority. As such, if the election results turn out as expected, India will be facing a hung parliament and the likelihood of a coalition government. The silver lining for the rupee is that unlike in 2014 it is blessed with low expectations this time around.

That currency traders have low expectations for Modi doesn’t mean, however, that the election outcome doesn’t contain significant risks. For example, if Modi surprises the markets and wins an outright majority again, the currency might rally based upon the idea that he will be able to accomplish reforms left undone during his first term in office. American and British readers of this article will be reminded that Reagan and Thatcher scored some of their biggest successes in their second terms.

At the other extreme, there is possibility of an outright Congress Party win, which was suggested in one, rather anomalous poll in January. This would suggest that voters want to send Modi’s reforms in reverse and would likely cause a short-term selloff in the currency.

Between these two extreme possibilities, there are several hues of a hung parliament. If the BJP falls just short of a majority, it will probably be able to cobble together a coalition that is amenable to his economic policies. This might result in a relief rally for the currency. By contrast, if Modi’s party wins more seats than anyone else but falls far short of a majority, the task of assembling a coalition and governing the country could become unwieldy and result in policy paralysis. That could be negative in the short term. That said, policy paralysis isn’t always a bad thing. Doing nothing is better than doing something counterproductive. American investors are accustomed to long periods of policy paralysis and have done just fine (1995-2000 and 2011-16).

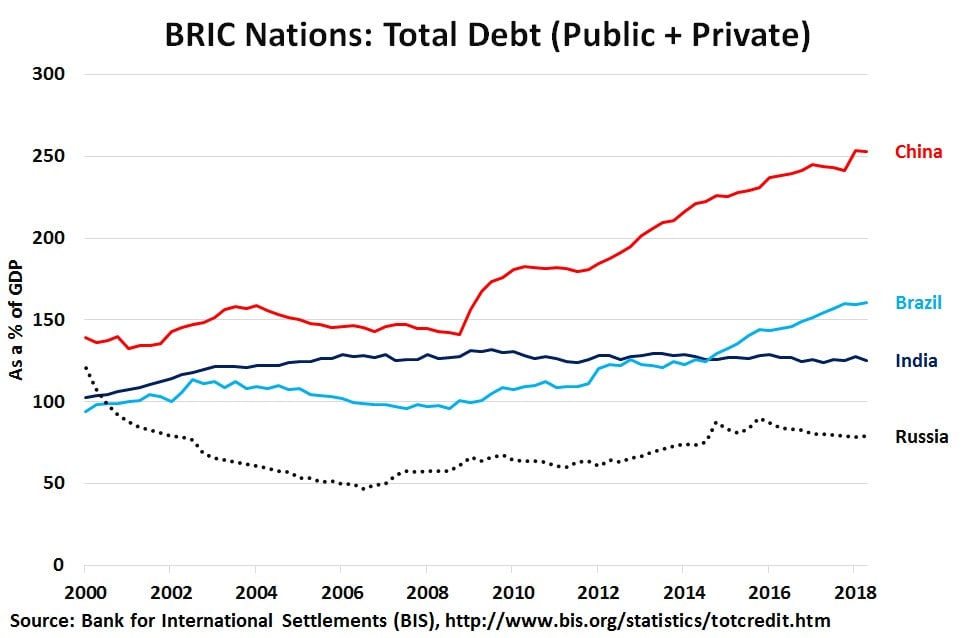

Outside of the election, India’s fundamentals look solid. Unlike China and Brazil, there has been no rise in overall debt (Figure 4) although government debt is a bit higher than it ideally should be. If China runs into serious trouble during the 2020s, India probably won’t be affected. For starters, India doesn’t export much to China and secondly, if China slows dramatically, it could be a disaster for commodity prices which is (mostly) beneficial for India as a big net importer of raw materials.

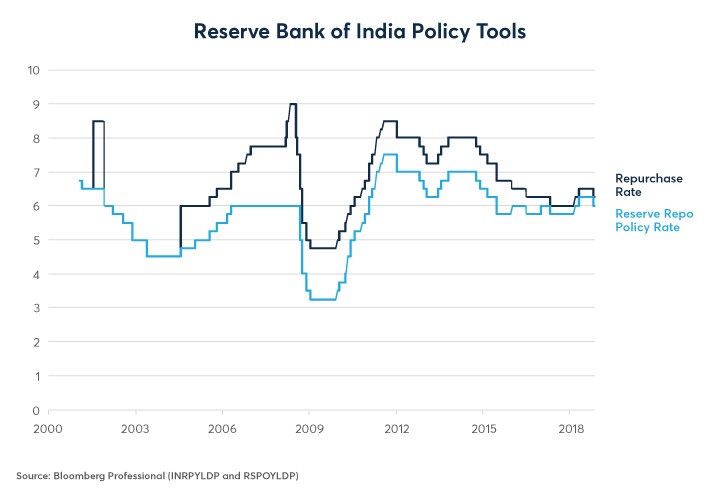

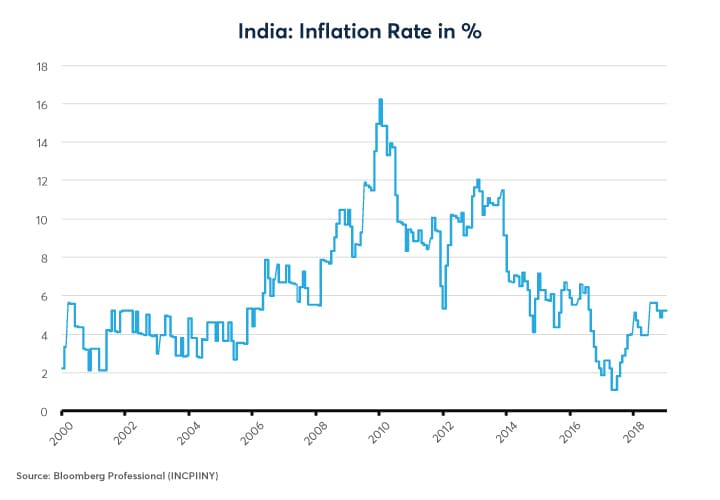

One item of concern, however, is the independence of monetary policy. On December 10, 2018, the Reserve Bank of India’s Governor Urjit Patel took the unusual step of resigning before his three-year term expired, apparently because of disagreements with Modi. Presumably, these disagreements concerned the tightness of monetary policy heading into the election. Indeed, Patel’s successor, Shaktikanta Das, cut rates in early February despite a modest rise in the rate of inflation (Figures 5 and 6). The currency market took this in stride. Even so, investors can be unforgiving of currencies whose central banks appear not to be independent. For their part, investors seem to see Das’s move as a one-off pre-election anomaly with little in the way of long-term consequences.

Bottom line:

- India’s election poses a significant event risk for the rupee.

- An outright Modi win could send the currency higher.

- A Congress win or a Modi victory far short of a majority would likely be trouble.

- The central bank may have been pressured into easing monetary policy at a time when inflation is rising.

- Otherwise, India’s economy looks healthy with solid growth and modest/stable levels of debt.

About the Author:

Erik Norland is Executive Director and Senior Economist of CME Group. He is responsible for generating economic analysis on global financial markets by identifying emerging trends, evaluating economic factors and forecasting their impact on CME Group and the company’s business strategy, and upon those who trade in its various markets. He is also one of CME Group’s spokespeople on global economic, financial and geopolitical conditions.

Erik Norland is Executive Director and Senior Economist of CME Group. He is responsible for generating economic analysis on global financial markets by identifying emerging trends, evaluating economic factors and forecasting their impact on CME Group and the company’s business strategy, and upon those who trade in its various markets. He is also one of CME Group’s spokespeople on global economic, financial and geopolitical conditions.

View more reports from Erik Norland, Executive Director and Senior Economist of CME Group.