By Anna Serruya: I have had quite the awakening these last couple of years. When I wrote and published the memo “Inflation Revisited” in September 2020, inflation was still way under the Federal Reserve’s 2 percent target, and the general understanding of inflation was that it was “something we had too little of”. Since then, it’s safe to say that “too little” quickly became “too much” and, if we are to believe ECB’s Christine Lagarde, something that came “out of nowhere”.

Amidst this, I believed that experiencing the consequences of loose fiscal and monetary policy would lead to a general understanding of what inflation really is. But, as it turns out, living through economic turmoil doesn’t automatically translate to decoding its mysteries. So here I am again to hold your hand through this learning journey about inflation. But there is no need to thank me; the pleasure is all mine.

I’ve been shaking my head as I see more and more people really believing that the top we saw in CPI last year was the first and last. When I asked for arguments as to why this secular inflation period would be the first time in history since the Federal Reserve started when CPI goes above 5 percent and only has one peak, the most compelling answer I got was this:

“The best argument is that there are ridiculously few data points. No statistician would make high-conviction predictions with that data. The burden of proof is on the people claiming that this is a repeatable pattern.”

Understand the future by studying the past

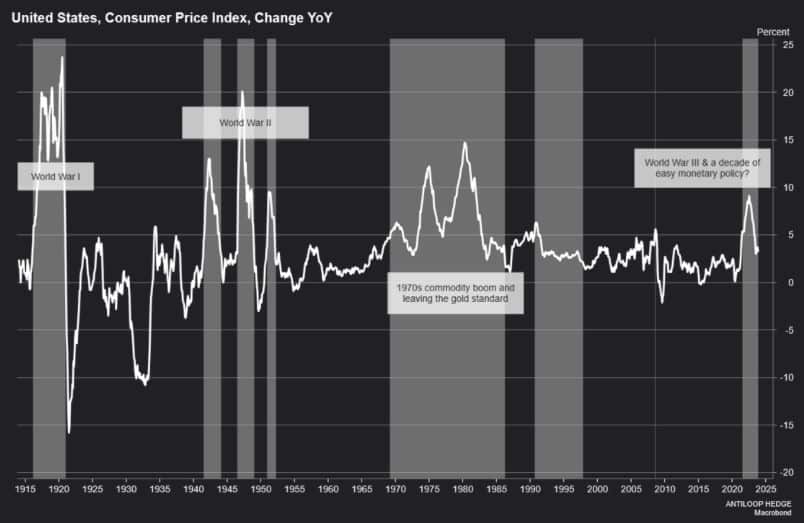

Even though the limited data points from the history of the US CPI since the inception of the Federal Reserve restrict the ability to make high-conviction statistical forecasts, it’s important not to dismiss the value of historical trends in guiding our understanding of potential future scenarios. While not a perfect predictor, history often leaves clues and patterns that can shape our forecasts.

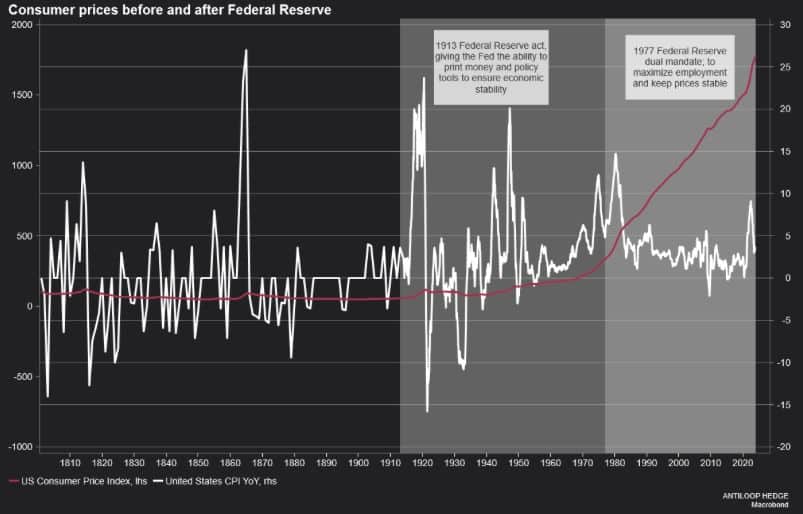

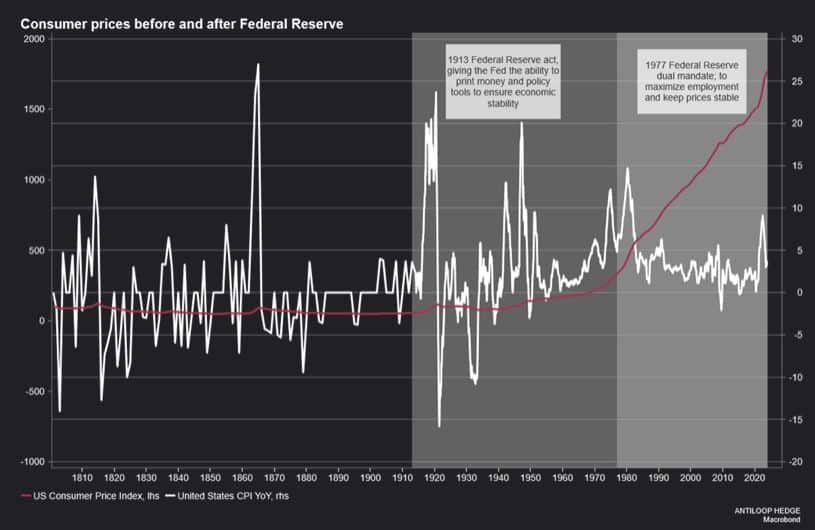

Moreover, while acknowledging the limitations in predictive accuracy, it’s notable that during the 110 years of the Federal Reserve’s existence, every instance of inflation surpassing 5% was followed by additional peaks. This observation, though not a statistical guarantee, suggests a pattern of recurrence that warrants attention.

But fine. Let’s look even further back to long before the bank that was supposed to help avoid deep recessions and economic downturns instead made cycles even worse.

If you have not already read my previous memo on what inflation really is (not what Central Banks today want us to think it is), I suggest reading it first. But, in short, inflation is the expansion of the monetary base, while deflation is the contraction of the same. Fluctuations in consumer prices are only the consequence of either expansion or contraction.

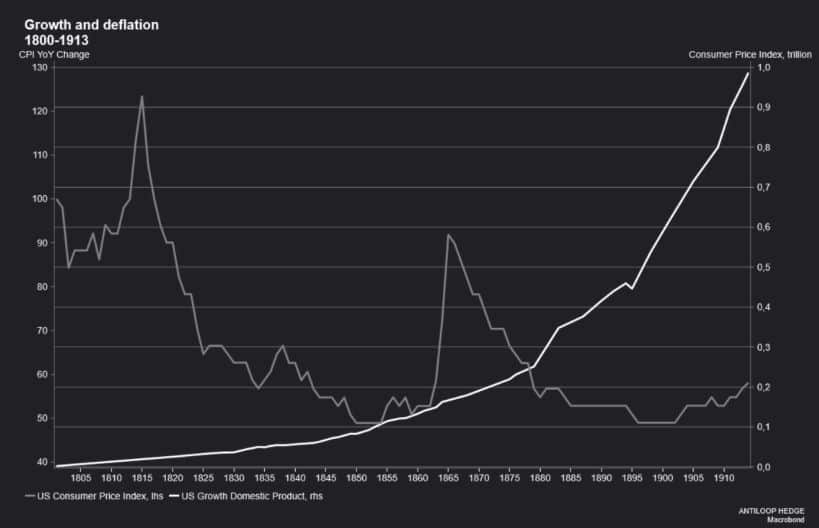

A century of falling prices and high economic growth followed by a decade of monetary expansion

Unlike the post-Federal Reserve period, consumer prices were relatively stable from 1800 to 1913. But, if we zoom in and focus solely on the 1800s, it becomes clear that it was a century of falling prices.

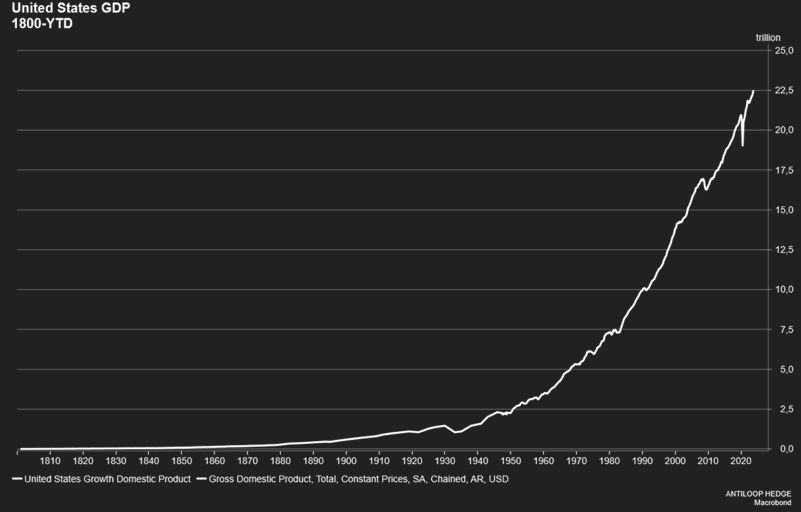

Falling prices, we have learned, are dangerous for the economy. With deflation, the economy can’t grow. But, that’s not entirely true, is it? Between 1800 and 1913, the US economy grew from 210 billion USD to almost 1 trillion USD simultaneously as consumer prices fell drastically. The reason behind the massive growth was the Industrial Revolution, leading to higher productivity growth than ever.

Since then, the United States’ real GDP has continued to grow from about 1 trillion USD in 1913 to 22,4 trillion USD today. That means that in the last 110 years, the US economy has expanded more than 22 times compared to 5 times between 1800-1913.

But what has been the main driver behind the accelerating growth, and what does that really mean for the economy?

Redefining growth

Redefining growth:

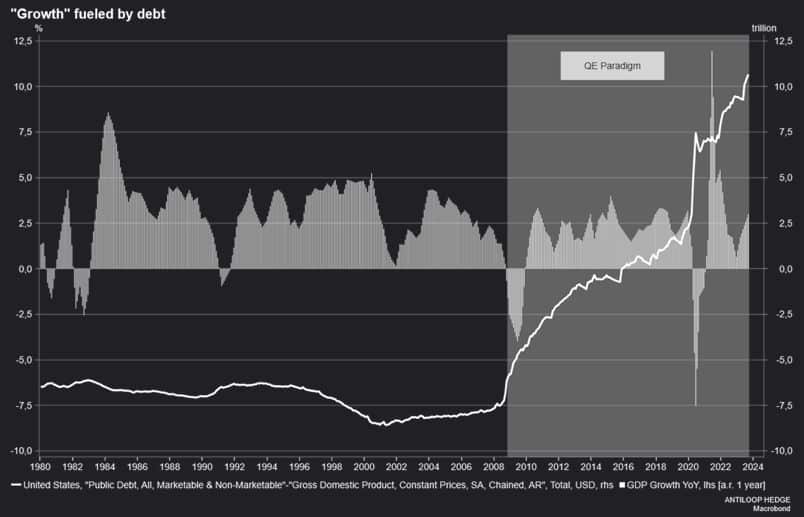

Is it really growth if the underlying driver is debt that has surpassed the value of the economy?

Debt is the real driver behind inflation, and one reason to believe there are more inflationary peaks ahead of us in time. A country’s gross domestic product should be adjusted for debt and should, in a healthy economy, both be higher and constantly grow.

Until 2008, the relationship between public debt and the real GDP of the United States was relatively stable. However, once the United States government got used to the fact that they could finance whatever however, the debt cycle spiraled out of control. Since then, we’ve been told that the US economy has prospered. Recovered. Grown. But, in reality, public debt has grown more than the economy, and in December 2015, public debt rose higher than the real GDP.

The chart below speaks clearly. Since Bernanke started QE during the financial crisis in 2008, there has been little economic growth adjusted for public debt, and the longer we let it continue, the worse it got.

Desire is the cause of suffering.

Argentina’s Mess – Our Future

As I wrote in the memo “Time: the perfect deflationary asset” in February 2021, Argentina’s mess is our future. At that time, I referred to the predicted consequences of more than a decade of easy monetary policy. Still, just now, something else that is just as important happened in the land of asado.

After decades of Peronism followed by raging inflation, a significant change has occurred. In November, the libertarian Javier Milei was elected the new president. Milei is everything the last president was not. When he, on the 10th of December 2023, took over the Baton from Alberto Fernández, he didn’t sugarcoat the state of the Argentinian economy when he held his first speech as President:

“There is no money. The political class left the country at the brink of its biggest crisis in history. We don’t desire the hard decisions that will need to be made in coming weeks, but lamentably, they didn’t leave us any option.”

What’s unfolding in Argentina paints a dramatic picture. It reveals a stark threshold in the tolerance of a nation’s people – a point where the escalating woes of inflation and rampant corruption become unbearable, igniting a fervent call for radical transformation. This shift in Argentina serves as a potent reminder of the power of public dissent and the inevitable demand for profound change when governance falters under the weight of economic and ethical decay.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not suggesting that the United States is on the verge of electing a capitalist minarchist as its leader. However, it is clear that the shift of power in Argentina is sending political shockwaves as more and more people are wondering what happened to their once-safe and predictable economy. The world is closely watching the development in Argentina as Milei is cleaning up the mess of the Peronists. And, if he succeeds, more countries will follow. Argentina is simply just ahead of the political and monetary curve.

Their mess is our future.

This memo has originally been published here.