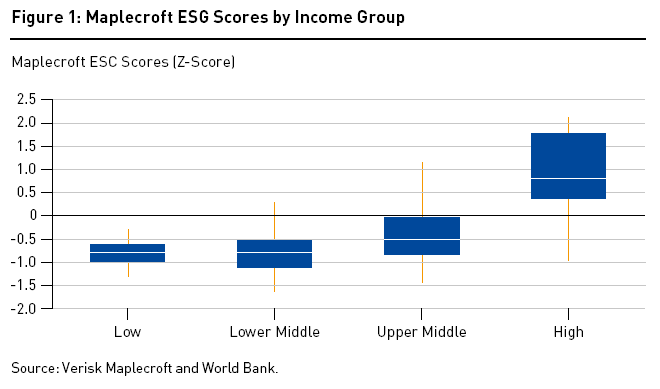

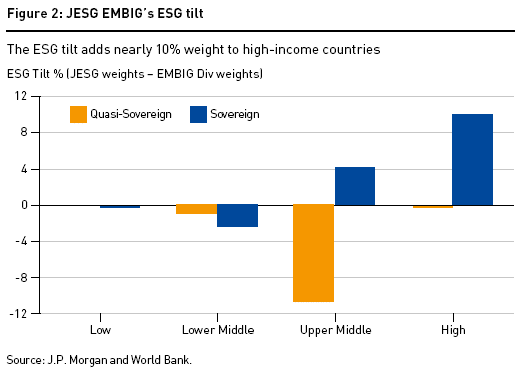

By Jens Nystedt, Oliver Faltin-Trager, Shikeb Farooqui, Joe Leadbetter, Mark Quandt – all EMSO Asset Management and Teal Emery (Teal Insights): ESG investing faces growing pains. ESG investing rapidly outgrew its origins in the equity market and spread to many other asset classes. Earlier this year, the World Bank warned that a naive application of ESG investing in sovereign fixed income markets could exacerbate SDG funding gaps1. Average Sovereign ESG scores have a near 90% correlation to a country’s level of income. Tilting investment portfolios by score levels that are so highly correlated with country income could have the perverse effect of skewing capital flows towards rich countries and away from developing economies with the most significant SDG funding gaps. In a follow-up paper, the World Bank outlines elements of a Sovereign ESG 2.0 that better balances purpose and profit2.

A. World Bank Findings

Diagnosis

Sovereign ESG deserves special consideration. Sovereigns fundamentally differ from corporations in size, function, and motivations. What E, S, and G mean in the context of sovereigns is different than for corporates.

Sovereign ESG scores do not quantify sustainability. Instead, sovereign ESG scores attempt to measure ESG factors that are financially material to a sovereign’s creditworthiness. In other words, a sovereign ESG rating examines which environmental, social, and governance factors affect a country’s willingness and ability to pay its debts in full and on time.

Considering ESG factors as an input to the investment process will not necessarily lead to progress on sustainability goals. Targeting purely higher sovereign ESG scores could exacerbate SDG funding gaps and incentivize investment in countries with higher per capita CO2 emissions3. Average sovereign ESG scores have a near 90% positive correlation with a country’s level of income. Investment practices or regulations incentivizing investing in countries with higher ESG scores could skew capital flows towards rich countries and away from poorer nations with the most significant development needs. Other common sovereign-level measures of sustainability such as the SDG Index, Notre Dame’s Global Adaptation Initiative Country Index (ND-GAIN), and the Yale Environmental Performance Index (EPI) are also highly correlated with a country’s level of income4.

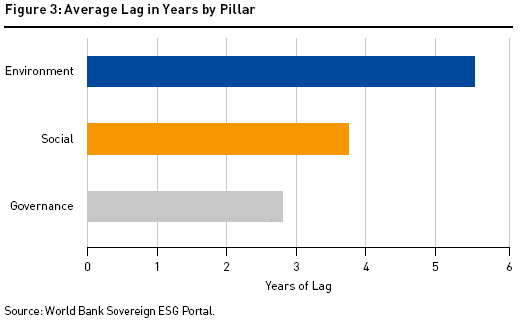

There is little agreement on what constitutes good sovereign environmental performance. The average correlation of the environmental pillar scores between data providers is 42% versus 85% for aggregate ESG scores. It is not easy measuring environmental progress if one cannot confidently measure actual performance.

Three challenges explain the divergence in environmental scores between data providers. First, broadly comparable sovereign-level environmental time series suffer from severe data gaps and lags. Creating estimates to fill those gaps and lags requires interpolation and extrapolation. Second, environmental scores may mix financial materiality with environmental materiality, resulting in an overall score that is difficult to interpret5. Third, climate risks are non-linear and likely to get worse in the future6 and as such, require forward-looking approaches with deep uncertainty.

B. Evaluating Emso’s Sovereign ESG Framework

B. Evaluating Emso’s Sovereign ESG Framework

Emso’s history of incorporating ESG into its investment process dates back many years, but has recently accelerated. As a component of fundamental fixed income investing, Emso has since our inception in 2000, put an emphasis on understanding governance factors. In recent years, we have tried to thoughtfully incorporate further select ESG factors into the research and investment process. We formalized our dedication to ESG with our first ESG policy in 2014 that guided incorporation of at least a minimal level of ESG into our investment process. We further codified our ESG integration by becoming a UN PRI signatory in 2015. Emso’s approach to ESG factors has evolved over the ensuing years as we have worked to devise a robust and substantive approach to ESG investing the emerging markets fixed income space.

Historically, Emso has focused on incorporating ESG factors that are financially material for asset prices, with a particular focus on governance factors over time. Taking an empirical approach to using ESG data has improved model accuracy across many of our medium-term fair value models, thereby enhancing our investment process and ultimately, we hope, our investment outcomes.

In line with the World Bank’s recommendations, our approach is forward-looking and emphasizes a country’s momentum. The framework that we utilize in our mandates which have an explicit ESG overlay allows for the inclusion of improving ESG stories that are not part of the J.P. Morgan JESG EMBI Index (JESG EMBI) if we believe that their ESG scores will improve above the threshold for inclusion in six to 12 months. The ingrained income bias with ESG scores tends to unduly reward high-income countries at the expense of low-income countries which are on the right track and, frankly, should be rewarded with marginal capital inflows. For example, despite the impressive efforts of the Angolan government to combat corruption and deliver meaningful structural reforms to the economy under its International Monetary Fund (IMF) program, Angola remains excluded from the JESG EMBI because it started from such a low base, and the data is lagging. We also believe that, within a total return framework, we should have the ability to short countries where the ESG scores are likely to deteriorate. For example, despite a clear deterioration in governance in Lebanon, it remains part of the JESG EMBI.

C. Where to go next in terms of ESG integration?

There is no free lunch; ESG as a factor in investing

We disagree with investors who propose that ESG considerations can always offer superior return performance, in addition to their positive impact: we believe there is no such thing as a free lunch. Adopting an ESG strategy will, by definition, decrease the size of the investment universe, reducing potential return drivers, at least over the short and medium term. For example, an investor may believe that taking a short position, or no position at all, in oil producers will produce higher risk-adjusted returns in the long term. However, they will have to accept a potential for short-term underperformance as oil prices fluctuate. Over a long-term investment horizon, we believe that giving ESG considerations a higher weight makes sense, but investors need to be aware that such considerations may not be reflected in asset prices anytime soon.

EM fixed income is still mostly pricing the capacity and willingness of a debtor to pay. To the extent that ESG considerations have an impact on these two factors, including them in any, whether explicitly an ESG overlay or not, could enhance investment returns, but there is no guarantee. Excluding poorly rated ESG issuers or overweighting positive ones is a style factor which historically has outperformed in some markets, while underperforming in others for many asset classes, including EM fixed income. Arguments made for ESG as a positive return driver in the short term are usually based on selective or limited data sets that do not have long enough cycles to assess. In EM fixed income, especially in local rates, ESG overlays that shift allocations to higher-rated issuers have also led to longer duration exposures, which has proved beneficial over the past few years, but not because of any ESG component.

Move towards outcome based instruments

At Emso, we are constantly on the lookout for better and more timely sources of ESG data. Data providers are putting increasing effort into providing improved ESG data for sovereigns and quasi-sovereigns. However, timely and relevant environmental coverage remains elusive. We are optimistic about geospatial technology which might significantly improve sovereign-level environmental data. Verisk Maplecroft, for example, have full spectrum coverage across all physical and natural capital risks at resolutions from <1km² to 22km². Larger firms are rapidly acquiring innovative ESG data start-ups. It will be important that new approaches are thoroughly vetted before being incorporated into existing product offerings and innovation is not halted prematurely. We remain very optimistic about the evolution and quality of ESG data, which means we would not want to tie ourselves down to any one data provider at this stage.

The rise of labelled bonds

Emso’s focus has so far been on integrating financially material ESG factors in its investment process across strategies. Labelled bonds, and sustainability-linked bonds provide a way to link investment with sustainability outcomes7. Whether green, blue, social, sustainable, or sustainably-linked, these instruments have seen a surge in investor interest over the last 18 months, but the lack of standardization and third-party monitoring still raises challenges of greenwashing and verification. These bonds cannot promise sustainability outcomes and a lot of work remains to adapt labelled bonds to a sovereign context.

Investor engagement the next frontier

Academic literature8 suggests that investor engagement is the most effective tool for driving the sustainability outcomes that end-investors increasingly expect. There remain open questions as to the most appropriate and effective areas for sovereign creditor ESG engagement, but we believe that progress is being made9. Traditionally, investors met mostly with economic policymakers in a finance ministry and central bank. Some sovereign debt issuers, proactively trying to adapt to the shift in investor sentiment towards sustainability, are beginning to facilitate investor dialogue with a wider set of policymakers on sustainability issues10.

Emso is currently actively involved at the working group level in the Investor Policy Dialogue on Deforestation (IPDD) which is a collaborative investor initiative established in July 2020 to engage with public agencies and industry associations in select countries on the issue of deforestation. Investors within this group recognize the crucial role that tropical forests and other types of natural vegetation play in tackling climate change, protecting biodiversity, and ensuring ecosystem services. As of July 2021, IPDD is supported by 54 global institutional investors from 18 countries. The coalition now represents approximately USD 7.2 trillion of AUM. The goal of the initiative is to coordinate a public policy dialogue on halting deforestation and to raise awareness within the investor community about deforestation trends and its impact. It also intends to present a stronger representative voice to regulators. The initiative started with Brazil, and as of January 2021, has expanded to include Indonesia.

E. Conclusion

At Emso, we will continue to strive to develop new and innovative ways to incorporate ESG across our strategies. We believe that our research presents a valid assessment of the potential trade-offs of ESG strategies. Our ESG framework has focused on integrating financially material ESG factors into the investment process. We integrate the data into our investment process via an econometric modelling framework that we believe allows us to improve investment outcomes. However, we acknowledge this approach utilizes ESG more as a risk mitigation tool than delivering on the UN’s SDGs or the Paris Climate Agreement targets. We believe that rather than overpromising what ESG led strategies can deliver, it is more fruitful to engage with asset owners on what goals they are planning to achieve (outcome based or financial materiality) and at what cost over the relevant investment horizon.

Looking ahead, we have taken stock of Emso’s Sovereign ESG framework to see how it aligns with the World Bank’s Sovereign ESG 2.0 framework. We are encouraged by the World Bank’s recommendation as it is very much in line with the direction that we are already heading. However, the World Bank’s approach also highlights ample room for improvement and suggests where we might want to go next. Data availability will remain an outstanding issue in our view, and it is useful to reiterate the need to avoid the ingrained income bias. Moreover, we think that the rapid surge in labelled bonds presents interesting, more outcome-based, opportunities for EM ESG investing. We see the most room for improvement in engagement; particularly between sovereigns, quasi-sovereigns, and investors. We see the work the IPDD is doing as a useful model, and we are looking for other areas where we can draw on their lessons and use it in other countries and contexts.

Finally, we believe that taking short positions in poor ESG performers is an important approach to reduce the costs of an ESG overlay; why should we only focus on “improving stories” when additional alpha opportunities can be identified by, for example, highly-rated ESG issuer reversing course? We see a role for taking short positions in any ESG based absolute or total return strategy.

- Gratcheva et. al. 2021b

- Gratcheva et al. 2021a

- Typically, richer countries tend to have higher emissions per capita, so just evaluating a country on pure ESG scores may result in higher per capita C02 emissions compared to a lower-rated ESG country.

- The World Bank research reports name this phenomenon “ingrained income bias”. See Gratcheva et al 2021b, p. 31-33.

- Boffo et al. 2020, “ESG Investing: Environmental Pillar Scoring and Reporting”, OECD Paris, www.oecd.org/finance/esg-investing-environmental-pillar-scoring-and-reporting.pdf.

- Bolton et al. 2020. “The Green Swan: Central Banking and Financial Stability in the Age of Climate Change.” Basel: BIS. https://www.bis.org/publ/othp31.pdf.

- See Boitreaud et al. 2021 p. 22-24 for a discussion of the relative strengths and drawbacks of labeled bonds from an asset manager perspective.

- Kölbel et al 2019

- Equity holders are partial owners of the companies they are invested in. Sovereign debt holders have a very different relationship with governments whose debt they own, meaning that the nature of engagement will be different and more limited in scope.

- The World Bank, as part of its advisory services, has provided guidance to debt management offices (DMOs) on engaging with investors on ESG issues. See Hussain et al 2020.

This article features in HedgeNordic’s 2021 “ESG & Alternative Investments” publication.