By Christoph Junge: Over the course of my career working with strategic asset allocation and alternative investments, I’ve often found myself reflecting on a simple question: What would I do differently if there were no constraints? No regulatory hurdles, no governance committees, no cost ceilings, no need for liquidity. Just the freedom to build the most effective portfolio possible in pursuit of long-term, risk-adjusted returns.

This thought experiment is more than idle curiosity. Institutional investors operate within a highly structured framework of constraints, some explicit, others implicit. Regulations, internal guidelines, reputational considerations, fee sensitivities, and the practical realities of board-level governance all shape the investment architecture. Most of these constraints exist for good reasons: they safeguard solvency, protect clients, and promote transparency. Yet they also limit access to certain strategies, reduce flexibility, and can lead to suboptimal portfolio design. Others are self-imposed or at least accepted, like tremendous focus on fees.

By contrasting today’s constrained reality with an unconstrained ideal, we can uncover the implicit trade-offs institutional investors make every day. What opportunities are we leaving on the table? Which constraints are genuinely necessary, and which are legacy artifacts that deserve to be re-examined?

In the following pages, I will outline the key constraints that shape institutional portfolio construction and then explore the design of a portfolio unconstrained by these limitations. The goal is not to disregard the realities of institutional investing, but rather to sharpen our understanding of how these constraints influence decision-making and identify opportunities to push boundaries in pursuit of maximizing the terminal wealth of beneficiaries.

As with any thought experiment, the true value lies not in the feasibility of the imagined outcome, but in the clarity, it brings to the world we live in.

To begin with, let us examine the most common constraints that shape institutional portfolios today, why they exist, how they influence portfolio construction, and what the landscape might look like if we could set them aside.

Table 1: Overview of Common Institutional Portfolio Constraints

| Constraint | Rationale | Impact on Portfolio | Unconstrained Alternative |

| Cost Sensitivity | Pressure to minimize fees; belief in low-cost beta; | Underweights high-fee alpha strategies (e.g. hedge funds, private equity) | Willing to pay high fees for high alpha or differentiated exposures |

| Liquidity Requirements | Need for regular redemptions (e.g. daily NAV); regulatory liquidity rules | Avoidance of illiquid assets; shorter time horizon; limited private market exposure | Embrace of illiquid strategies (e.g. VC, real assets, private credit) |

| Governance Complexity | Senior Management or Board may lack time or expertise to assess complex products | Preference for simple, transparent strategies; benchmark-driven investing | Portfolio includes complex, opaque but effective strategies (e.g. ILS & CTAs) |

| Time Horizon Misalignment | Performance often judged on short-term results despite long-term liabilities | Herding behavior; aversion to short-term drawdowns and peer risk | Patience for long-term payoffs; tolerance for temporary underperformance |

| Regulatory Constraints | Investment restrictions (e.g. MiFID II, UCITS, Solvency II) | Limited alternative asset allocation due to prohibitive capital charge; limited product offering for private clients | No regulatory ceilings; free use of leverage, derivatives and alternative investments |

| Capacity Constraints | Too much capital to deploy efficiently in niche strategies | Underexposure to high-alpha, low-capacity strategies (e.g. small-cap value, frontier EM, certain hedge fund strategies) | Access to boutique managers and esoteric strategies |

| Benchmark Constraints | Career risk and evaluation against peers or indices | Benchmark hugging; constrained tracking error; reduced peer tracking error tolerance | Absolute return focus; no benchmark anchoring |

| Reputation / Headline Risk | Aversion to negative press or politically sensitive investments | Avoidance of controversial areas (e.g. ESG-sensitive sectors, hedge funds, commodities) | Opportunistic allocation, unconcerned with optics if risk-adjusted return justifies it |

With the institutional constraints laid out, we now turn to the core of the thought experiment: If all those limitations disappeared, if we could construct a portfolio governed solely by investment merit, what would it look like?

The most immediate shift in an unconstrained portfolio would be a significantly higher allocation to illiquid assets – not because I was Head of Alternatives in my previous role but because the capital market assumptions of leading institutions are highly favorable for these types of asset classes. Without cost sensitivity, the need to meet short-term liquidity demands or comply with solvency metrics, one could allocate far more capital to private equity, venture capital, real assets, and private credit to harvest the complexity and illiquidity premia embedded in these types of investment.

Cost sensitivity is often framed as prudence. However, in a portfolio unconstrained by fee caps, implementation would prioritize net-of-fee outcomes over optics. For instance, a 2-and-20 buyout fund would be entirely justifiable if it delivered net returns exceeding those of listed equities. Even the Medallion Fund by Renaissance Technologies, despite its steep 5% management fee and 44% performance fee, would remain a compelling choice (if it was open to external investors), given its exceptional net-of-fee performance.

This opens the door to a full embrace of active management, especially in less efficient markets. In a truly unconstrained context, indexing would remain a useful tool for certain markets, but not a default. The implementation lens would shift from “How cheap is it?” to “How valuable is it?”

In parallel, we would likely see greater use of diversifying strategies with low correlation to traditional risk factors. CTAs (managed futures) and insurance-linked securities, often overlooked due to their complexity or headline risk, could play a central role as portfolio stabilizers.

In a constrained world, scale and simplicity often trump alpha. Large institutions cannot meaningfully deploy capital into small-cap value in emerging markets, niche hedge funds, or local distressed credit managers. But if capital and capacity constraints were lifted, these high-alpha, hard-to-access areas would gain prominence.

Institutional investors often claim to be long-term but operate under significant short-term pressures. Monthly performance rankings against peer groups, critical newspaper articles, rolling three-year track records and ultimately clients shifting to another provider after periods of underperformance. Freed from these pressures, an unconstrained investor could adopt genuine long-term patience. A long-horizon investor could allocate heavily into dislocated markets or out-of-favor sectors without fear of tracking error or career risk.

Characteristics of the unconstrained portfolio

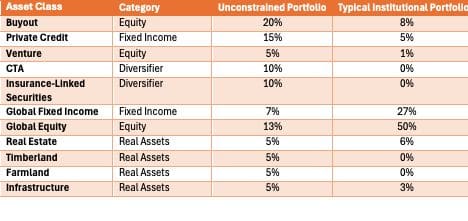

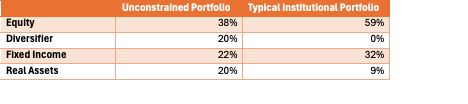

To highlight the stark contrast between a typical institutional portfolio and an unconstrained portfolio, we can examine the figures in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2: Asset Allocation weights of Unconstrained Portfolio vs. a typical Institutional Portfolio

It quickly becomes evident that institutional portfolios heavily allocate to equity risk, while real assets, an essential hedge against inflation, and strong diversifiers (CTAs and ILS) remain underweighted compared to an unconstrained approach. The unconstrained portfolio seems like a more balanced approach.

Table 3: Asset allocation grouped into categories

Having sketched the architecture of a portfolio free from institutional constraints, we now turn to its defining features.

High tolerance for complexity

The unconstrained portfolio is unapologetically complex. It leverages a wide variety of strategies: private markets, insurance-linked securities, managed futures. This complexity is not pursued for its own sake, but because it expands the opportunity set and enhances risk-adjusted returns. Whereas constrained investors often favor simplicity for governance reasons (e.g., ease of explanation, board-level oversight), the unconstrained allocator can embrace complexity – as long as it is paired with genuine insight and manager oversight.

Illiquidity as a feature, not a bug

Illiquidity is traditionally framed as a risk, but in the unconstrained portfolio, it is reframed as a source of return. The portfolio is not designed for daily mark-to-market pricing or redemptions; it is designed for long-term capital compounding. This allows it to harvest the illiquidity and complexity premia across private equity, real assets, and private credit in a size that is typically not possible to many institutions due to regulatory or internal constraints.

Benchmark agnostic

The unconstrained investor is not concerned with tracking error or peer group rankings. Success is not defined relative to a benchmark, but in terms of achieving absolute returns with favorable downside characteristics. The focus shifts from “how do I compare?” to “how do I compound?”

True diversification

Diversification is more than just spreading capital across traditional asset classes. The unconstrained portfolio actively seeks uncorrelated or counter-cyclical strategies, especially those with positive convexity in crisis periods, like managed futures. Unconventional strategies like insurance-linked securities may be difficult to govern or justify, but they can shine with uncorrelated returns when traditional portfolios suffer. This results in a portfolio that is better equipped for regime change and less reliant on central bank tailwinds.

These portfolio characteristics indicate theoretical advantages, but theory alone is not enough. To truly validate this approach, we must examine historical performance and assess how an unconstrained portfolio has fared in real-world market conditions.

The historical results are also in favor of the unconstrained approach, as shown in figure 1. The unconstrained portfolio outperforms the traditional portfolio by 72,8% since 2007, equal to 1,3% p.a. – and this is after fees for most of the alternative asset classes. To account for the few asset classes reporting gross of fees returns, we would have to subtract app. 25 bps. p.a. – still a massive outperformance.

The standard deviation is nearly cut in half, but this must be taken with a large grain of salt as this is influenced by the smoothing effect of unlisted asset classes. However, not all downside protection comes from the smoothing effect as for example the diversifier bucket (which are liquid and hence not subject to smoothing) delivered outstanding returns in 2022 – a year where both equities and traditional fixed income suffered.

Figure 1: Historical performance evaluation of the unconstrained vs. the typical institutional portfolio

Past performance is not indicative of future results.

Conclusion

This thought experiment began with a simple question: What would an institutional portfolio look like if we removed all constraints? The answer, as we’ve seen, is not a fantasyland of speculative bets or unlimited risk-taking. On the contrary, it is a portfolio defined by better diversification and downside protection, delivering superior returns, albeit one unconstrained by the operational, political, and regulatory realities that shape most institutional mandates.

Of course, most institutional investors cannot (and should not) adopt a fully unconstrained approach. Regulations must be respected, governance frameworks upheld, and liquidity needs met. Yet the value of this exercise lies precisely in what it reveals: by stepping outside the current structure, we can see more clearly where that structure is helpful and where it may be unintentionally limiting.

What makes this exercise valuable is not the impracticality of the unconstrained ideal, but the contrast it provides. It shines a light on what we may be missing, what we might be overemphasizing, and where we could rethink legacy practices. In particular, it challenges us to ask:

- Are we forgoing long-term returns in pursuit of short-term optics?

- Are our governance processes enabling intelligent risk-taking or stifling it?

- Are we mistaking simplicity for prudence, and liquidity for safety?

Few institutions will ever operate without constraints, but every institution can benefit from periodically stepping outside its own mental models. The more clearly we understand the trade-offs we’re making, the better we can decide which constraints to respect, which to challenge, and where we might push past convention to build better portfolios for the long term.

About the author

Christoph Junge is the founder of Alternative Investments Research & Education, providing courses and consulting services in Alternative Investments. Previously, he served as Head of Alternative Investments at Velliv, a major Danish pension fund, and has extensive experience in Asset Allocation, Manager Selection, and Investment Advisory from roles at Nordea, Tryg, and Jyske Bank. He holds the Chartered Alternative Investment Analyst (CAIA) designation and brings more than two decades of experience from the financial sectors of Denmark and Germany. He is a sought-after speaker and advisor, known for combining deep industry expertise with a practical, forward-looking approach to investing.