By Edward Hoyle and Harry Moore – Man AHL: Incorporating an often-overlooked asset class into a sustainable multi-asset portfolio.

While fossil fuel use is a principal source of greenhouse gas emissions, other commodities will be central to the transition to cleaner energy.

Introduction

Much of the effort in sustainable investing to date has been focused on identifying companies with sustainable businesses, with a view to investing in their stock or bonds. Multi-asset sustainable investing must go beyond this, but the path forward is not well trodden. In this paper, the first in our ‘Path Less Travelled’ series focused on multi-asset sustainable investing, we consider investing responsibly in commodities.

We believe commodities will play a crucial role in achieving net-zero targets; while fossil fuel use is a principal source of greenhouse gas emissions, other commodities will be central to the transition to cleaner energy. Commodities can offer investors benefits through diversification and their positive sensitivity to inflation but the absence of a widely accepted framework to evaluate the ESG characteristics of the asset class acts as a barrier for many. In this paper, we seek to contribute to addressing this challenge, focusing on three main areas:

- Considerations when investing in commodities

- The diversifying role of commodities in a portfolio

- The environmental and social characteristics of commodities

1. Considerations when investing in commodities

Commodity prices are influenced by supply as well as demand, with storage costs and benefits associated with utilisation leading to the “convenience yield” in forward prices. Difficulties in storage and transportation make trading in physical commodities a specialist endeavour so here we will focus specifically on investing in commodity futures, which, by extension, covers investment routes such as indexation.

There are two important aspects to consider in relation to commodities: production and utilisation.

There are two important aspects to consider in relation to commodities: production and utilisation. The production of commodities not only damages the environment but can also have a negative social impact. Incidents of poor labour practices have been recorded, including dangerous working environments, the exploitation of child labour, poor pay and forced labour. Further, social damage can result from land grabbing, environmental poisoning and, in the case of livestock production, preventative antibiotic use (which can accelerate microbial resistance). While the utilisation of commodities generally has a negative environmental impact, there are some positive environmental use cases, especially relating to the transition away from fossil fuels to renewable energy. The social impact of utilisation is more often positive given commodities are necessary to support life. Crops and livestock are required for food, economic growth is supported by energy consumption through manufacturing and transport, and energy powers domestic heating.

Production and utilisation directly relate to physical commodities. This opens the debate as to whether trading commodity derivatives (such as futures) can have a tangible influence on the physical-world issues of environmental and social impact. We believe that derivatives can play an important role through risk sharing. Trading futures can impact physical commodities through influence on spot prices and hedging costs for consumers and producers. Commodity futures contracts are generally deliverable, which means that a contract held to maturity is settled by the delivery of physical commodities. Most futures contracts are not held to maturity, precisely to avoid this physical exchange. However, the link between futures and physical commodities is a fundamental one, with speculation in short-dated futures contracts potentially affecting spot prices – both upwards and downwards. Producers and consumers may use futures markets to hedge the price that they sell and buy commodities in the future (hence the name). Speculators can help balance the hedging demand between producers and consumers by shouldering some of the price risk. In other words, speculators acting in the market can offer liquidity and risk-sharing to commercial hedgers, helping them manage their revenues or costs. In this regard, speculator activity is important for markets to function. However, an excess of speculation can itself cause imbalance by forcing forward prices too far from fundamentals. In these cases, whether prices are driven too high or too low will either favour producers over consumers or vice versa. Excess speculation could also increase market volatility, which potentially increases hedging costs for both consumers and producers through higher margin costs.

Tradeable commodities

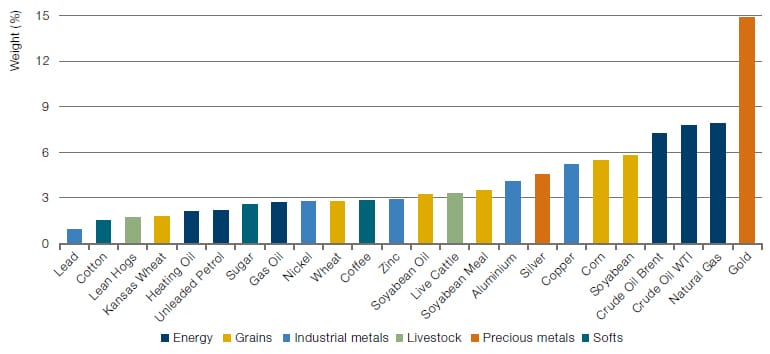

In the sections that follow, we shall focus on the Bloomberg Commodity Index (BCOM) and its constituents. BCOM is an index of commodities futures prices, with over $110 billion estimated to be tracking it [1]. We show the 2023 target weights of BCOM by commodity and by subsector in Figure 1. While gold has by far the largest individual weight in the index, energy is the largest subsector.

Figure 1. BCOM target weights by commodity

Figure 2. BCOM target weights by subsector

Why allocate to commodities in a long-only portfolio? Our answer is liquidity, diversification, and inflation protection.

2. The diversifying role of commodities in a portfolio

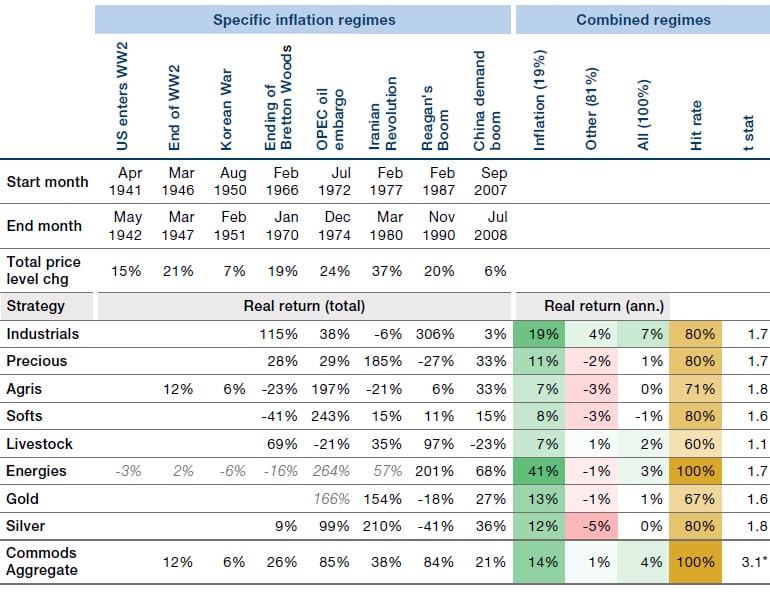

The rolling of futures contracts earns a yield, which may be positive or negative depending on the factors described above. A positive roll yield is associated with “backwardation”, a downward sloping forward curve, and a negative roll yield is associated with “contango”, an upward sloping forward curve. Forward curves evolve through time, including switching between backwardation and contango. This implies dynamic risk premia that may be positive or negative [2]. So why allocate to commodities in a long-only portfolio? Our answer is liquidity, diversification, and inflation protection. We see this as a single case, rather than three separate arguments. Commodity prices are typically an input into headline inflation numbers, with empirical evidence demonstrating that commodities perform well during inflationary episodes [3] (see Table 1). There are admittedly other ways to protect a portfolio against inflation, including inflation-linked bonds and inflation swaps. However, alternatives to commodities tend to be less liquid and consequently more expensive to trade.

Risk premia in commodity markets may vary through time, but that does not mean that holding a diversified basket of commodities has a negative long-run return. The long-run correlation of commodities to traditional assets such as stocks and bonds is low. So, commodities provide diversification, and improved diversification allows investors to take additional risk exposure without increasing portfolio tail risks [4]. In summary, commodities can provide diversification and a liquid defence against inflation, without the long-run costs associated with buying hedges with options.

Table 1. Commodity futures returns during historical US inflationary episodes and annualised returns during inflationary and non-inflationary times

3. The environmental and social characteristics of commodities

When evaluating the ESG characteristics of commodities, it is – of course – necessary to consider the negative impact of production. But, as referenced earlier in this paper, it is important to balance this with utilisation, which may be positive.

Commodities have an important place in multi-asset portfolios but are also essential for the transition to a low-carbon economy.

Commodities and their role in the transition to a low-carbon economy

Commodities have an important place in multi-asset portfolios but are also essential for the transition to a low-carbon economy. Commodity production is unquestionably damaging for the environment and the use of commodities may have a negative environmental impact, particularly in the case of fossil fuels. However, utilisation is necessary to sustain life, and it can also be a force for environmental good. The transition to a low-carbon economy requires investment in infrastructure to produce, transport and store renewable energy [5]. Key renewable energy processes such as wind turbines or solar panels produce electricity at source. Batteries thereby become an important storage option and transportation is primarily through electrical wiring. This places industrial metals at the centre of the energy transition, given they are required for infrastructure expansion in each of production, transport and storage. The heterogeneity of commodities is apparent even within the precious-metals subsector. Silver, despite being classified as a precious metal, has important industrial applications (particularly in solar panel production), and so also plays an important role in the energy transition while gold is less important.

Orderly metals futures markets can provide producers and consumers with an opportunity to efficiently hedge their exposure to price changes.

Agricultural commodities

Investment in agricultural commodities, even via futures markets, is a sensitive and sometimes controversial topic [6]. It is a basic human right to have enough food to sustain a healthy life. The poorest in society are most likely to have this right breached, with food price volatility being a potential cause. The transmission of price volatility from short-term speculation to the prices of staple foods at the point of sale could lead to negative social outcomes. However, evidence for such transmission is mixed and effects confused further by governmental interventions, such as price controls [7].

A further distinction can be made between commodity index investing and futures speculation. It is difficult to find evidence that commodity index investing affects future agricultural futures prices [8]. Ultimately, these risks can be mitigated by orderly, liquid markets, with a large number and variety (producers, consumers, market makers, index investors, speculators) of agents. With liquidity comes low cost of arbitrage, and hence a closer adherence of prices to fundamentals. Also, without access to risk sharing across agent types, the cost of food production could rise. Sustainable expansion in food production should be encouraged, and this may be facilitated through hedging of future price moves.

Quantifying the sustainability of commodities

Reinhard Friesenbichler Business Consulting (rfu) has developed a methodology for quantifying the sustainability of commodities [8]. Their scores combine the environmental and social impacts of production and utilisation. The precise weighting between production and utilisation varies by commodity, but typically just over half the weight goes to production.

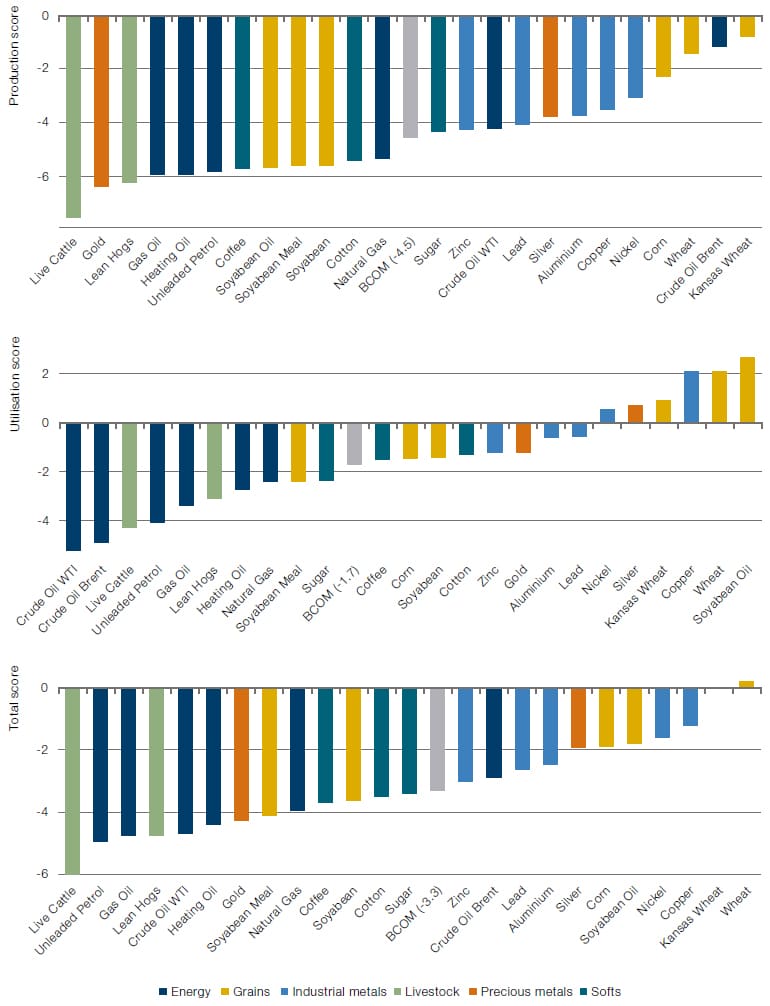

In Figure 3, we show the rfu production, utilisation, and overall scores for each commodity, which lie between the values -10 and +10. We include values for BCOM, which we derived by weighting the individual commodity scores according to their 2023 BCOM target weights. It is perhaps not surprising that the production score for every commodity in BCOM is negative. The very negative production scores for live cattle (beef) and lean hogs (pork) partly relate to abusive labour practices, deforestation, microbial antibiotic resistance, and animal cruelty. Live cattle also has a very high carbon footprint relative to other foodstuffs. Gold production is associated with abusive labour practices and environmental poisoning and has a large carbon footprint relative to other metals. Soy products and coffee are also linked to abusive labour practices, deforestation, biodiversity loss and environmental poisoning from pesticide use.

We can construct a more sustainable portfolio of commodities than BCOM by focusing investment in certain metals and grains.

In utilisation scores, fossil fuels score very negatively due to associated CO2 emissions. Live cattle and lean hogs are almost exclusively used for food, but there are serious health risks linked to red meat consumption, and global consumption is highly unequal. Soymeal is predominately used as animal feed, and so its utilisation is directly linked to livestock production. It consequently has a poor utilisation score, whereas its cousin soybean oil has a positive score as a commonly used vegetable oil for human consumption. Industrial metals and silver appear towards the right of the figure, with their higher utilisation scores in part due to their importance for the energy transition, as discussed above.

Overall, we can construct a more sustainable portfolio of commodities than BCOM by focusing investment in certain metals and grains, although investment in the latter is somewhat complicated by the possible impact on food prices.

Next, we focus on a basket of metals that are important for the transition to renewable energy, comparing it to BCOM.

Figure 3: rfu production, utilisation, and overall (total) scores for BCOM commodities

Commodity returns are driven by both supply and demand factors.

Impact on returns

As we have established, BCOM is diversified across commodity subsectors. It may be more sustainable to allocate only to those commodities critical to the energy transition, such as industrial metals and silver, but this will result in different returns. Commodity returns are driven by both supply and demand factors. While energy, the largest sector in BCOM, and metals share some common demand drivers – particularly those related to economic activity – their supply dynamics are quite different.

We created a Metals index by allocating 77.6% to the Bloomberg Industrial Metals Subindex and 22.4% to the Bloomberg Silver Subindex, with monthly rebalancing. We chose these weights to be in proportion with the 2023 target weights of industrial metals and silver in BCOM. In Figure 4 we compare the returns of BCOM with our Metals index. The returns are 66% correlated. The Metals index has higher returns than BCOM over the period, but is also more volatile (20.1% versus 14.7%, annualised).

Figure 4. Returns of BCOM index and a weighted combination of the Bloomberg Industrial Metals Subindex and the Bloomberg Silver Subindex (Metals)

Emissions allowances

We have seen that nearly all the commodities in BCOM are given negative sustainability scores by rfu. Our calculations score the whole BCOM as -3.3. This raises the question as to whether there are instruments with emphatically positive sustainability scores that are sensitive to inflationary forces. Emissions allowances offer a potential answer. Increased demand is likely to trigger both higher prices (inflation) and greater industrial activity (supply). Rising industrial activity can then lead to a rising market price of emissions allowances and potentially further inflation. Higher market prices of allowances can provide investors with some inflation protection, act as a disincentive for industry to pollute, and promote energy efficiency and sustainable manufacturing.

Figure 5 shows rfu sustainability scores for three tradable emissions allowances: the California Carbon Allowance (CCA), European Emission Allowance (EUA) and Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI). RGGI covers electricity production from fossil fuels in the northeast of the US. RGGI’s utilisation score is slightly negative due to its low effectiveness in disincentivising emissions due to pricing and coverage. RGGI only covers CO2 emissions, whereas CCA and EUA cover a broader range of greenhouse gases.

Figure 5: Production, utilisation and total rfu scores for emissions allowances

Conclusion

Commodity utilisation is necessary to support humanity and will play a key role in the transition to renewable energy. Commodities can also play an important role in a multi-asset portfolio, providing diversification and inflation protection. However, they are often overlooked in responsible investing due to difficulty in assessing their ESG characteristics. Establishing a relationship between commonly traded commodity derivatives (e.g. futures) and physical commodities is the first hurdle, since it is physical commodities that are actually produced and utilised, and so have an environmental and social impact. We believe that risk sharing provides this link as speculators bear some of the price risk associated with an imbalance between future supply and demand. While some consider speculation in commodity markets controversial, we see clear social and economic benefits to orderly futures markets. Building on the research of rfu, we demonstrate how a commodity index can be evaluated based on sustainability criteria, and how the sustainability of a commodity investment can be improved (a) through more targeted investment in commodity subsectors, and (b) by expanding the investment scope to include emissions allowances.

Bibliography

[1] Bloomberg, “Bloomberg Commodity Index 2023 Target Weights Announced (press release),” 27 October 2022. [Online]. Available: company/press/bloomberg-commodity-index-2023-target-weights-announced/.

[2] C. B. Erb and C. R. Harvey, “The Strategic and Tactical Value of Commodity Futures,”Financial Analysts Journal, vol. 62, no. 2, p. 69–97, 2006.

[3] H. Neville, T. Draaisma, B. Funnell, C. R. Harvey and O. van Hemert, “The Best Strategies for Inflationary Times,” The Journal of Portfolio Management, vol. 47, no. 8, August 2021.

[4] T. Abou Zeid, “Leverage Does Not Equal Risk,” Man Institute, 2022.

[5] S. Desmyter, O. van Hemert, A. K. Muthusamy, M. Goldklang, E. Cole and A. Preston, “Climate Investment: Positioning Portfolios for a Warmer World,” Man Institute, 2021.

[6] I. Knoepfel and D. Imbert, “The Responsible Investor’s Guide to Commodities: An overview of best practices across commodity-exposed asset classes,” onValues Ltd, 2011.

[7] M. Robles, M. Torero and J. von Braun, “When Speculation Matters,” IFPRI, 2009.

[8] J. D. Hamilton and J. C. Wu, “Effects of index-fund investing on commodity futures prices,” International Economic Review, vol. 56, no. 1, p. 187–205, 2015.

[9] Reinhard Friesenbichler Business Consulting, “rfu Sustainability Rating for Commodities: Methodology Description,” 2022.