By Andrew Beer, Co-Founder of DBi and Co-Portfolio Manager: The problem with managed futures ETFs is not that they don’t work well. It’s that they’re working too well.

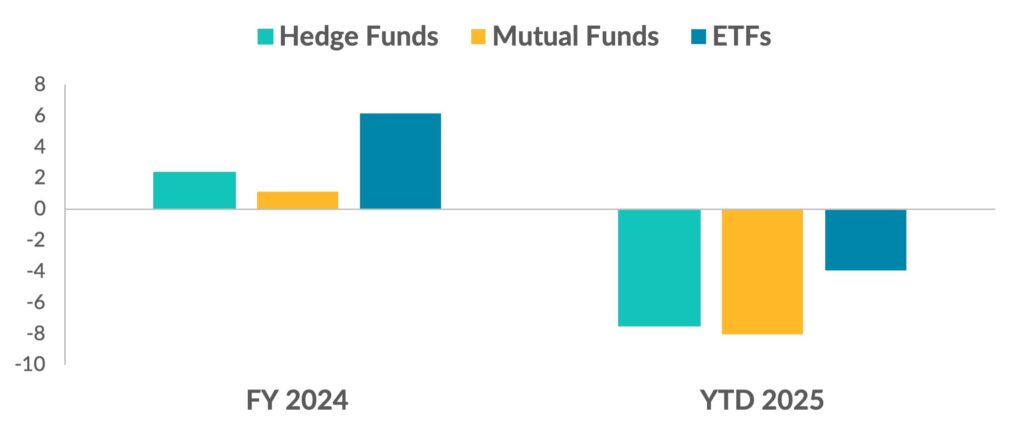

In both 2024 and 2025 (through July), managed futures ETFs materially outperformed more expensive hedge funds and mutual funds. Cumulatively over the past 19 months, the average ETF has outperformed hedge fund and mutual fund peers by a rather staggering 730 bps and 900 bps, respectively. Through a different lens, 85% of ETFs outperformed in 2024 and 90% are doing so this year:

This is an awkward outcome, to say the least, for the CTA establishment. Managers of hedge funds and mutual funds, as well as many of their clients, often have denigrated ETFs as “too simple.” One manager described it as buying a “knock off Louis Vuitton bag from a street vendor.” Another confidently claimed that “no ETF will ever outperform hedge funds.” Managers who offer ETFs alongside mutual funds and/or hedge funds often claim they “save the best stuff” for the latter.

It’s important to frame these criticisms in historical context. Dial back to the 1990s, and the CTA space was called, to use a repugnant term, a “fee orgy.” High net worth investors paid 10% a year for products pushed by aggressive brokers. Guaranteed return products were guaranteed to have egregious embedded fees. Then by the 2000s institutional allocators caught the bug, and the space evolved into a “hedge fund allocation” – without a second thought, 2/20 became the norm. Then the first wave of mutual funds tacked another 1% on top.

The high fee model has been under attack since 2010. First, AQR – the “fair fee hedge fund guys” – launched an “institutional quality” mutual fund with an expense ratio dangerously close to 1% flat; AlphaSimplex, then owned by Natixis, soon followed. Within a few years, banks were pitching simple trend following indices that could be accessed via derivatives at even lower price points. During the Long Winter of the late 2010s, institutional allocators turned the screws on managers to obtain steep fee breaks. Then our firm showed up with a straightforward, ten factor replication model that seeks to outperform by hundreds of bps purely through efficiency. Each innovation was met with strident criticism.

“The high fee model has been under attack since 2010. During the Long Winter of the late 2010s, institutional allocators turned the screws on managers to obtain steep fee breaks.”

In response to this threat from “commoditization,” many established firms have sought to differentiate through complexity. Trading hundreds of markets, including many on the fringe, sounds like it should generate better returns. Faster models sound like they should get into the best trades earlier and limit losses during the inevitable reversal. Sophisticated risk management tools sound like they should curtail losses during painful whipsaws. It’s a pitch that has worked well with allocators. After all, more features are supposed to mean more alpha.

Yet, at least in recent years, the extra alpha doesn’t seem to be there. The great question today is whether this is a fluke or a structural issue. There are two issues to consider.

First, was the rush to complexity a mistake? The complexity pitch has always stood on thin ice. Fringe markets do not appear to “trend more,” which raises questions of where and how managers can extract excess returns. Noisy markets tend to knock short term models out of profitable trades – with the discouraging result that Sharpe ratios can drop perilously to zero. Tight risk management cuts both ways: valuable de-risking during some inflection points, but a tendency to get head faked by “vol spikes.” In the absence of the threat from lower cost products, would sensible managers have added these features?

A second, and related, issue is implementation costs, or “slippage.” Simply put, this is the difference between what your model does in theory and practice. Some costs are easy to calculate: “explicit costs” are just the commissions paid to buy and sell futures contracts during the year. Others are much thornier: “implicit costs” are the price move “ripples” that occur when large managers enter and exit positions. BestEx Research, a well-respected provider of execution algorithms, estimates the latter at 3-5x the former. This is not a new issue: a decade ago, managers bragged about bringing down “slippage” from 400 bps to 200 bps. The irony of the rush to complexity is that it may have inadvertently unwound those efficiency gains.

“The growth of managed futures ETFs is bringing an indisputably valuable strategy to an untapped pool of investors.”

The data above should prompt allocators to ask hard questions about these two issues. How precisely do managers estimate implementation costs or slippage? How much have portfolio-level costs risen in recent years? How do they vary from the most liquid to least liquid markets they trade? Why is it realistic to believe that a given modeling enhancement, or new fringe market, can clear such a high hurdle? Did complexity backfire this year – for instance, a risk management tripwire that forced an unwind in a thinly traded market?

The growth of managed futures ETFs is bringing an indisputably valuable strategy to an untapped pool of investors. Interestingly, though, the recent outperformance might have inadvertently shined a light on a larger question:

In the managed futures space, do simpler, cheaper and more efficient ETFs just work better?